The recent repeal of the Caesar Act may be viewed as a diplomatic triumph, but it does little to address the profound economic challenges facing Syria. Industrial collapse, agricultural crisis, uncontrolled urbanization—lifting sanctions alone will provide temporary relief, not lasting solutions, without comprehensive reforms.

Article published (in French) on October 24, 2025, in Conflits

On October 10, the United States Senate repealed the Caesar Act, which prohibited all aid, investments, and transactions with the Syrian government and related businesses. Al-Sharaa celebrated this move as a diplomatic success and an important step towards rebuilding the country. By the end of 2025, financial exchanges between Syria and the global community are expected to resume.

The resuscitation of Syria’s economy is a formidable task, requiring not only a conducive atmosphere but also the restoration of faith among business owners and financiers. Ahmad Al-Sharaa has highlighted sanctions as the primary hindrance to economic recovery. However, his policies and capabilities remain questionable.

The Decline of Syria’s Manufacturing Sector

Syria’s industrial sector has experienced a significant decline, leading to a decrease in production and job opportunities. The war and subsequent economic sanctions have exacerbated the situation, further straining an already struggling industry.

Islamists have a penchant for free-market economics, favoring commerce over manufacturing and farming. They favor trade over industry and agriculture, as did Muhammad. As a result, when they were briefly in power in Egypt and Tunisia, production collapsed, with an increase in trading, including smuggling. [1]

Syria’s market was inundated with duty-free goods from Turkey as early as December 2024, effectively shutting down the majority of the country’s factories that had managed to survive the conflict. The impact is particularly severe in Aleppo, Syria’s industrial hub. The Sheikh Najar industrial zone was completely plundered by rebels in 2012, and the city endured a five-year siege of unparalleled violence that forced the economic elite to flee to Turkey, the Gulf, and Egypt.

Textile business owners in Aleppo moved their manufacturing facilities to Egypt and Turkey, taking advantage of the region’s political stability and access to vast consumer markets through free trade zones. They do not intend to return to Syria, as investing in this industry requires long-term visibility, which is currently lacking.

The skilled workforce that once formed the foundation of Syrian industry has dissipated. These workers either followed their employers to Turkey and Egypt or fled to Germany. The manufacturing landscape that had been cultivated over the years in Syria’s urban centers was obliterated by the conflict, and its rebuilding will require at least a generation.

Government Action in Favor of Trade

Starting in January 2025, the port of Latakia experienced a significant surge in traffic. The worth of imports has tripled, while that of exports has grown by an impressive 60%.[3] The catalyst for this trade boom is attributed to the implementation of exchange rate liberalization, the abolition of customs duties, and the elimination of cumbersome administrative hurdles. This development has brought immense joy to the merchant community, as evidenced by the importation of tens of thousands of used cars in the last eight months, with a declared value exceeding $3 billion. [4]

Previously, the importation of automobiles in Syria was tightly regulated and subject to significant taxes. However, due to a fourfold decrease in their value, the dream of owning a car has become more accessible for many Syrians. Additionally, there is encouraging news regarding the overall decline in prices for mobile phones, computers, solar panels, and various other imported items. To benefit from these resources, one must have access to them. The divide between those who receive aid from a foreign relative and those who solely rely on local resources is substantial.

Indeed, public sector salaries have quadrupled, rising from $20 a month to $80 due to Qatar’s and Saudi Arabia’s contributions. Despite this, it is still not enough to enjoy a comfortable life, as the cost of essential items has increased due to the end of fuel and food subsidies.

However, these salary increases have helped fight corruption. Everyone we encountered, from ordinary people to business owners, highlighted the positive changes in their interactions with the authorities and law enforcement. The advancement has sparked optimism that the economic situation will improve for all once the sanctions are lifted. The underlying issues affecting various industries, including agriculture, which remains a crucial income generator for at least a third of the population, are often overlooked.

Water Scarcity Threatens the Country

Syrian agriculture is extremely dependent on rainfall. However, the country is experiencing three years of drought. Overexploitation of groundwater, due to a lack of regulation, has led to a gradual decline in water levels.

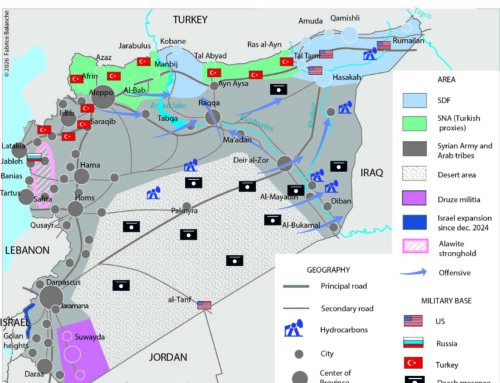

In the northeastern region, Turkey is allowing less water to flow into Syria. This reduces irrigated land. This is a long-term, structural issue, rather than a temporary problem, as farmers and authorities may believe.

The reality is that climate change is a pressing concern for Syrian agriculture, requiring adaptation to water scarcity. To address this challenge, the state must invest in advanced water treatment and irrigation system modernization.

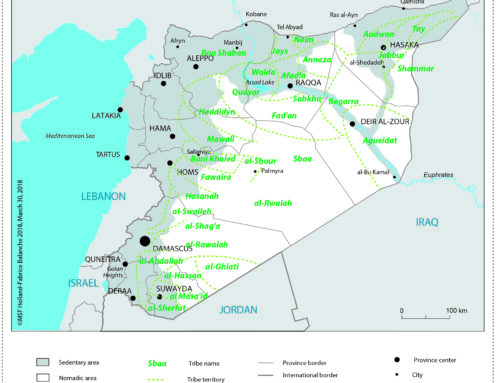

During the war, farmers ignored regulations on the use of groundwater resources. Many illegal wells were dug, draining groundwater. It is essential to implement strict measures to protect this vital resource. However, the new administration is cautious not to upset rural communities, where tribes have significant influence. In addition, the cost of these investments is prohibitive: billions of dollars. No lender is willing to take on such a risky project.

To ensure the country’s food security, the Syrian government is counting on regaining control over the northeast, currently in the hands of the Syrian Democratic Forces. This region used to be Syria’s breadbasket, guaranteeing its grain independence. [5] However, today, production has collapsed, forcing the leaders of the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (AANES) to import flour for the region’s 3 million people.

The water supply for irrigating the Euphrates perimeter has become inadequate, while groundwater is overused and drying up.

Moreover, the agricultural production system has become chaotic. Since subsidies ended, farmers have reduced or eliminated the use of fertilizers. The exorbitant cost of fuel for pumping water has severely restricted irrigation outside of areas served by rivers. Consequently, crop output has plummeted, decreasing from more than 50 quintals per hectare pre-war in irrigated regions to a mere 20 quintals currently.[6]

In the arid farming regions, farmers are increasingly choosing oats over wheat due to the guarantee of a marketable yield for livestock farmers. Conversely, sowing wheat carries the risk of a complete loss if the drought persists.

The rural exodus continues indefatigably toward the impoverished suburbs of Syria’s major cities, where they subsist on odd jobs and international aid.

City Reconstruction is Haphazard

The devastation in Syrian cities is catastrophic. As a result, there are few new construction sites. Instead, some people have returned to their damaged homes and are making repairs as they can. However, entire neighborhoods, such as Jobar and Daraya, located on the outskirts of Damascus, remain in ruins, and their rehabilitation necessarily involves their complete demolition.

But how can those who deserve compensation receive it? Residents of this region think that the Gulf States will intervene generously in Syria.

Homs’s Khaldyeh District remains stuck in a state of perpetual stasis, eagerly awaiting the arrival of a benefactor who will transform it into a “Victory Boulevard” as promised on billboards. Indeed, the revitalization of certain neighborhoods can be a source of economic prosperity, as was the case with downtown Beirut in the 1990s.

Unfortunately, these peripheral and disadvantaged regions only interest developers if they can create upscale residential communities in them. The working classes are increasingly living in informal settlements that are expanding uncontrollably, as urban planning regulations have not been enforced since December 2024. The new government understands that access to housing is a prerequisite for social stability. As a result, it has chosen to tolerate unlawful housing development.

The water and sewage systems are severely damaged. Syrians must buy drinking water and household water. On average, these costs account for around 20% of a family’s income. As a result, some people have had to stop buying drinking water and use contaminated water, either from delivery trucks or straight from the taps. Non-governmental organizations (NGOs) are working to restore water treatment plants, but they do not have enough resources to repair the networks. As a result, the water leaving the plant is no longer safe to drink when it reaches the residents’ homes. [8]

The cost of renovating urban infrastructure is simply prohibitive. The state does not have the means or the will to do so. This situation creates opportunities for the private sector to develop gated communities offering amenities unavailable elsewhere in the city. This attracts the upper classes and the Syrian diaspora, who want to invest there, as is already the case in Iraq and Egypt.

In these two countries, political leaders are closely tied to real estate developers and benefit financially from the expansion of gated communities. For this reason, they have no interest in renovating urban centers or restoring public services. The deterioration of these services has made people move to new, private neighborhoods.

The evolution of urban areas reflects the growing social divide due to conflict, diminishing government power, and increased uncertainty.

[1] Ben Néfissa Sarah and Vermeren Pierre, Les Frères musulmans à l’épreuve du pouvoir, Paris, Odile Jacob, 2024, p.193

[2] Interview with Mr X, Aleppo, September 2025.

[3] Interview with Mr Y, Latakia, September 2025.

[4] Zaman Amberin, “Syria’s business elite embrace Sharaa, push for Caesar sanctions repeal”, Al-Monitor, 16 October 2025, https://www.al-monitor.com/originals/2025/10/syrias-business-elite-embrace-sharaa-push-caesar-sanctions-repeal

[5] Balanche Fabrice, « Le nord-est syrien : les enjeux du grenier à blé », Carto n°51, november-december 2018.https://www.areion24.news/2019/02/12/le-nord-est-syrien-les-enjeux-du-grenier-a-ble/

[6] Interviews with farmers in North Eastern Syria (2017-2024)

[7] Munqeth Othman Agh, “ Is Syria on the Recovery Path?”, ISPI, 3 October 2025 https://www.ispionline.it/en/publication/is-syria-on-the-recovery-path-218429

[8] Interview with a French NGO, Raqqa, January 2022.